This was the first time the gap had been less than 20% since the onset of the pandemic, and August 2021's footfall was 20% ahead of August 2020, despite the government's controversial Eat Out to Help Out scheme encouraging consumers to spend in restaurants.

Still, the August 2021 numbers showed high street footfall down 23.5% on pre-pandemic levels, shopping centres off by 24% and retail parks 2.4% lower, with London continuing to suffer more than most thanks to a lack of foreign tourists and office workers. Shopping visits in the capital were down by 38% on 2019, albeit this was an improvement on July when numbers were 50.4% down. The improvement is expected to continue this month as more people head back to the office and restrictions on foreign travel begin to ease.

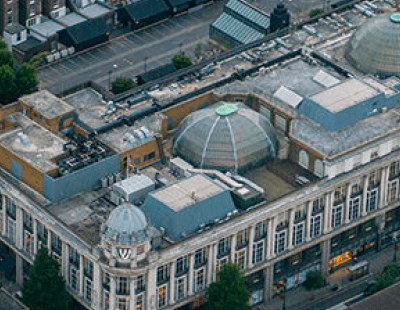

But with shopping centres still struggling, are there alternative uses for these often mammoth structures? How easy, for example, is it to convert a shopping centre for residential use?

Here, PIT carries out a Q&A with Raymond Fang, a senior associate in Goodwin’s Real Estate Industry group, to discuss the changes that he is seeing in retail-related real estate, in particular shopping centres, in the aftermath of the pandemic.

How are shopping centres adapting their business models to make them more resilient as their popularity seemingly fades? Is residential part of this repurposing?

Physical retail is in a phase of evolution, driven by a variety of factors linked to the rise of e-commerce, including advances in logistics technology, more informed consumers, increased product choices, and lowered barriers to entry. The pandemic and the growing dependence of online marketplaces has accelerated this evolution, and this is especially true for shopping centres, which have been forced to adapt at pace or risk permanent closure.

One strategy has been to diversify and reduce exposure to retail, replacing or supplementing traditional tenants with residential (especially Build to Rent (BTR)), co-working and traditional community services – this is especially attractive for shopping centres that are centrally located and well connected to transport.

Another strategy being explored by UK shopping centre owners is to repurpose parts of shopping centres that are currently underutilised to better serve contemporary local needs. Integrated community hubs on shopping centre sites may include low-tech logistics facilities for last mile delivery services (this is popular at the moment for companies like Weezy, Dija, Zapp, Gorillas and Jiffy, all battling for business in the 10-15 min local grocery delivery market), flexible office space, parking bays for micro-mobility solutions (used by companies like ZipCar, Lime, Tier and Dott), electric vehicle charging stations, pop-up facilities like health clinics and farmers' markets, neighbourhood dark kitchens and urban farms.

Explain to us what dark kitchens and urban farms are...

Deliveroo, Uber Eats, Just East, DoorDash, etc, thrived during the pandemic as eat-in restaurants were forced to close. This accelerated the trend of dark kitchens (also known as ghost or cloud kitchens), which are delivery-only restaurants.

Dark kitchens can be independently owned, but most are increasingly owned directly by the food delivery companies themselves, like Deliveroo, which fits out and then licences dark kitchens directly to operators on flexible terms and with shared facilities. This eliminates upfront capex and other overhead expenses for a restaurant business.

Other exclusive operators of dark kitchens have raised significant capital in recent months, including Karma Kitchen, which raised over £250 million in their latest private fundraising.

Meanwhile, urban farms involve the growth of fruits, vegetables and herbs in urban areas as a commercial enterprise. Supporters tout urban farms as a necessary solution for high-density living, allowing the localised cultivation and distribution of food in urban areas, using warehouse space and new techniques like vertical farming where plants are arranged in a stacked formation and grown in micro-controlled environments, in some cases without soil.

Again, there is a significant amount of seed and venture capital flowing into the urban farms sector, especially to support new technology that enables these businesses to succeed.

Both dark kitchens and urban farms thrive in underutilised spaces in population centres.

How could shopping centres be converted to include housing? Are there complications?

Recent legislation has broadened and streamlined the ability to change a building’s use status from retail to residential in England. This has given developers and investors an opportunity to rejuvenate dying high streets by replacing failing businesses with new homes.

However, in comparison to high streets, it can be a lot more complex to introduce residential to shopping centres, where existing architecture and planning considerations need significant repurposing to balance the different needs of shoppers, residents and service vehicles.

Increasingly, shopping centre owners are considering joint venture or other partnership arrangements with residential developers with the required know how to explore this potential. This may include building apartments on top of unused carparks and loading docks, and/or converting underutilised upper retail floors to living space while retaining essential retail like ground-level supermarkets.

How can this repurposing be carried out in a green, sustainable way?

Repurposing and reusing existing buildings, and other light touch interventions (like keeping existing underground carparks for shoppers, residents and other visitors), will almost always result in the use of fewer building materials and the release of less carbon compared to a ground up development.

Developers are also increasingly sourcing sustainable building materials (like responsibly harvested timber and recycled steel), introducing green energy solutions (like solar roof panels), and vertical gardens serviced by recycled water (these “green walls” can absorb carbon dioxide, insulate against noise, reduce building heat absorption, and improve thermal insultation thereby reducing a building’s energy cost).

Additional shopping centre specific considerations include dedicating repurposed space for local resident activities and grassroot organisations, for example to host charity events or exhibitions for local artists, which can help sites co-exist with communities in a sustainable way.

Why would homes on these locations be attractive to investors, landlord buyers and tenants?

These days it takes a brave investor to see opportunity in existing retail (other than for repurposing or as part of distressed opportunities), with capital values and rents in the sector having been on a downward decline for many years now.

Contrastingly, residential BTR has generated glowing returns for investors, with tenant demand continuing to outstrip supply. Investors have been further drawn to BTR as an asset class during the pandemic, with average rent collection rates remaining close to 100% and average rental growth continuing to rise.

BTR in the context of shopping centres is no exception, with mixed-use developments being viewed as significantly more attractive for investors looking for a stable income stream compared to pure retail.

In addition, the pandemic has further emphasised the trend of decentralisation and the growth of the '20 minute community', where residents have everything needed to live, consume, work and play within a 20-minute radius. At the right scale, a shopping centre redevelopment has the ability to provide a blended living solution where consumption, living, work (in the form of shared office space), social and leisure options exist alongside each other, which is an attractive proposition for tenants, landlord buyers and institutional investors alike.

What role is Goodwin playing in the next evolution of shopping centres?

Goodwin has long been the leading firm at the intersection of capital, innovation and disruption. Our dedicated Real Estate Industry and PropTech teams can advise institutional global and local investors, landlords and developers exploring the next phase of retail’s evolution towards a model of co-existence with other core and alternative asset classes, including by the use of technology.

Our cross-discipline teams advise on fundraisings, financings, joint ventures, direct and indirect acquisitions, developments, and restructuring and distressed situations, in relation to all operational and non-operational real estate asset classes, including retail and residential.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.png)

.jpg)

Join the conversation

Be the first to comment (please use the comment box below)

Please login to comment